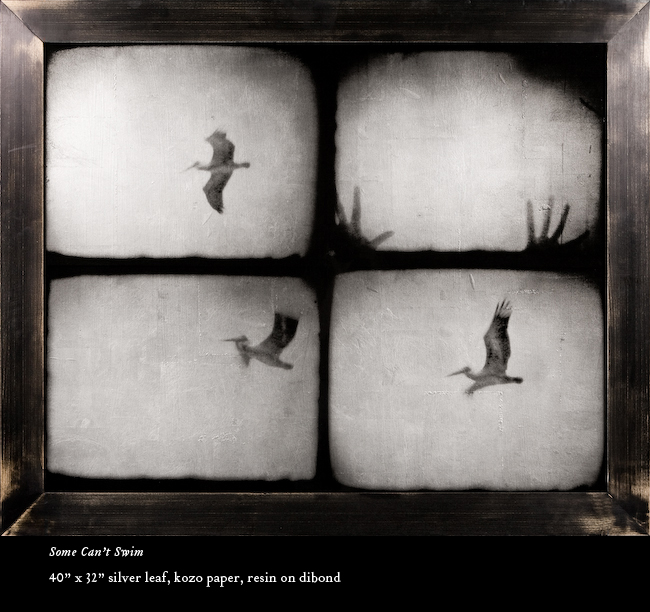

The picture is an old-fashioned sepia-toned photograph. (Indeed it is silver leaf, kozo paper, resin on dibond.) It is divided into four window panes. First to take hold of our attention is the pelican, gliding, its wings tilting toward us. In the panel below its wings are raised. Head back in noble profile, the pelican powerfully flaps. And one frame over, the great bird soars. The picture recalls Muybridge’s zoopraxiscopic animations, wherein an animal’s natural motion, broken up into stills, becomes strange and uncannily fascinating. Now the picture seems divided into story frames, the story of flight.

But now notice the last frame (above, over on the right). We at first mistook it for a close up of the bird’s wing-tips, the largest longest-extended feathers, diving out of the frame. But on second look, we see that these are human appendages, two hands held up, extended into the sky. The rest of the body has sunk below. These hands are a downing man’s last grasp for life.

The title of the picture, by New Orleans based photographers Louviere + Vanessa, is “Some Can’t Swim.” Pelicans, of course, can swim. Some people, however, cannot. The pelican flies over, perhaps sees something splashing in the water below, but noticing that whatever it is cannot be a fish, not something to eat, something too large, strange, awkwardly out of its element, it flies on. So the picture becomes an image of the world’s indifference, like Breugel’s ”Landscape with the Fall of Icarus.” The extended human hands, desperate silhouettes, disappear into the blackness that separates the panes and frames the entire picture. These borders seem about to constrict, to dilate closed like the end of a scene in an old silent film. The charred black between the panels seems conspicuous now: the darkness makes a cross. This cross is no symbol of salvation, but an emphatic crossing out. So it poignantly recalls the ancient Egyptian image of the pelican with its “power of prophesying a safe passage for a dead person in the Underworld.”