Of the total 37 plays by William Shakespeare that I’ve resolved to see this year, the 400th anniversary of his death, “Measure for Measure” is my second (I’ll post about the first later). Performed in Russian by the Pushkin Theatre of Moscow with original verse supertitled above Chicago Shakespeare’s main stage, this “Measure” was directed by Britain-based Cheek by Jowl’s Declan Donnellan and designed by Nick Ormerod. An array of bare light bulbs, recalling interrogation, but so many as to imply a surveillance state, hang above a steeply sloped stage with three monumental red cubes. Stage left from the darkness between the cubes, enter shuffling a huddled mass of folk led by a tall gaunt figure in filthy rags with a shaved head and a faraway stare. (This specter-like figure will remain a mystery until near the last act.) Now he leads the group — the cast of police, bureaucrats, prostitutes, a pimp, a friar, a novice — wandering about the stage and around the cubes. One character steps out from the mass of people. It is the Duke. The drama begins.

Throughout the play, characters flock together and flow apart, allowing for swift seamless transitions between scenes and cohering the action into a dream-like pantomime. The cast as a single moving mass, of course, represents the polis, the city, the people, those of Elizabethan England, of Putin’s Russia, and, of course, us of Rahm’s Chicago. (In fact, Mayor Emmanuel sat ten feet from me at last Saturday’s performance. He looked good, all considering, our embattled Duke.)

The opening premise of “Measure for Measure,” I think must be inspired by the “murderous Machiavel.” Here’s the pertinent passage from The Prince:

“The next point is worthy of note, and of imitation by others; […] When the duke took over [the district], he found it had been controlled by impotent masters, who […] had given [the people] more reason for strife than unity, so that the whole province was full of robbers, feuds and lawlessness of every description. To establish peace and reduce the land to obedience, he decided good government was needed; and he named […] a cruel and vigorous man, to whom he gave absolute powers. In short order this man pacified and unified the whole district […]. But then the duke decided such excessive authority was no longer necessary, and feared it might become odious […] And because he knew that the recent harshness had generated some hatred, in order to clear the minds of the people and gain them over to his cause completely, he determined to make plain that whatever cruelty has occurred had come, not from him, but from the brutal character of the minister…” (Chapter VII “About New States Acquired with Other People’s Arms and by Good Luck”)

Just so, the Duke of Vienna absences himself, leaving hard-assed Angelo in charge to mete out tough justice. Angelo abuses his power when incited to lust by the purity and beauty of novice Isabella, pleading mercy for her brother, convicted fornicator Claudio, sentenced to be executed. The Duke spies upon his dukedom incognito as a monk and elaborately schemes to right the wrongs of Angelo. His plan involves a scripted political rally, a quick-switch bed-trick, and a faux execution. For the latter, however, he requires a human head. Enter the wretched wraith from the play’s opening. This is the Duke’s proposed scapegoat, Barnardine.

Barnardine is described as a Bohemian, a prisoner of nine years but, under the severe administration of Angelo, to be soon executed. Barnardine, however, while admitting his crime, refuses to repent: “A man that apprehends death no more dreadfully but as a drunken sleep: careless, reckless, and fearless of what’s past, present or to come, insensible of mortality and desperately mortal” (IV, ii, 131-4) The state is ready to put the man to death, but no one wants to send his unshriven soul to hell. The Duke in his guise as friar tries to reconcile “desperately mortal” Barnardine to repentance and so to the promised paradise post-axe, but the prisoner remains unwilling: “I swear I will not die today for any man’s persuasion.” (IV, iii, 52-3)

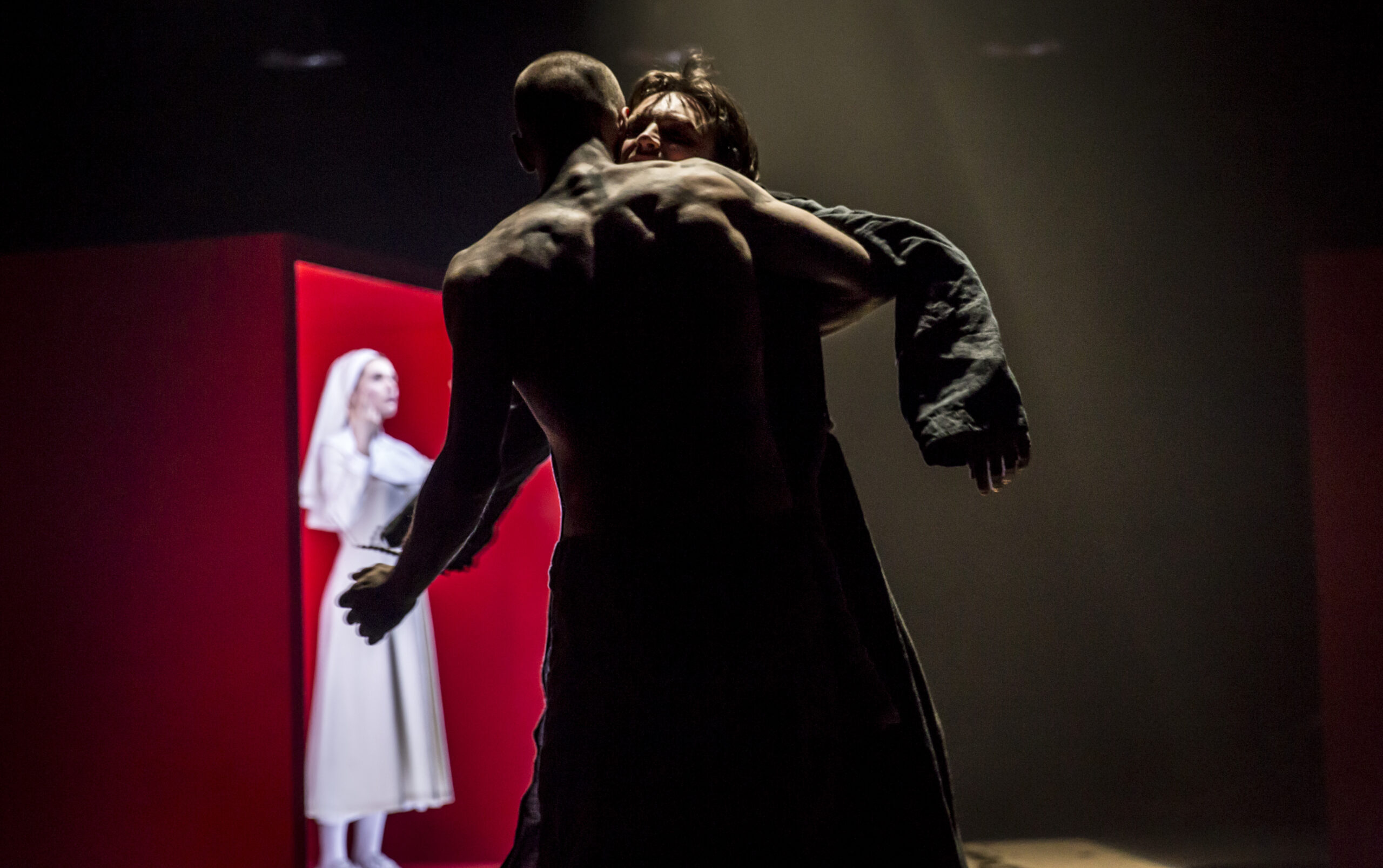

It is here that this extraordinary production exposes this problem play’s madly beating heart. Stymying the Duke’s manipulations and digressing from its own fast-flowing narration, Barnardine and the Duke embrace and begin to waltz. They spin across the stage and, as the music takes on a manic edge, the great red cubes upstage rotate to reveal neon-lit tableau, a triptych. Here is the condemned fornicator Claudio strapped into an electric chair. There is the brutal pimp, Pompey vigorously raping one of his whores. In the middle is Isabella the tempting virgin, her palms extended in recollection of the crucifixion. It is Christ, once again, between the criminals. Is dancing Barnardine another Barabas, and the Duke, another Pilate? What’s the meaning of this waltz?

“Measure for Measure” certainly plays with the Gospels’ themes: “For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.” (Matthew 7:2) I wonder, however, if its title is to be interpreted ironically.

When the music stops, the Duke admits that Barnadine is “A creature unprepared, unmeet for death,/ And to transport him in the mind he is/ Were damnable.” (IV, iii, 60-2) The Duke, who thought like Machiavelli that he could scheme and manipulate his way to justice, now throws up his hands in desperation. But then, just then, God (or Shakespeare) grants a miracle: serendipitously dead of fever comes the fresh corpse of a pirate (in alpine Austria?!). “O, ‘tis an accident that Heaven provides!” (IV, iii, 70) So now the Duke has his head, the necessary prop for his fake execution. And I wonder how well the just-witnessed dance macabre illuminates the insane fiat of Shakespeare’s plot. Like the bloody head in a plastic bag soon brought on stage, our Golgotha-waltz is gratuitous, like life, like death, like sex, like forgiveness. After all, what can account for Isabella at the end of the play forgiving Angelo? There is no method, no measure, to this madness.

This problem play ends like a traditional comedy with weddings and dancing. The couplings, however, are ambivalent. Claudio and his bride are already with child; Angelo has been paired with a woman he’s been tricked to bed; and the Duke proffers his hand to Isabella whose discomfort with sensual love is still palpable.

Machiavelli’s original tale ends theatrically too, but his is Grand Guignol: “… to make plain that whatever cruelty had occurred had come, not from him, but from the brutal character of the minister. Taking proper occasion, therefore, [the duke] had [the minister] placed on the public square[…] one morning, in two pieces, with a piece of wood beside him and a bloody knife. The ferocity of this scene left the people at once stunned and satisfied.”

How does this profound Russian production of “Measure for Measure” leave us? The still unrepentant Barnardine leaps off the stage to be lost among us, a stranger among strangers. And the unhappy couples on stage spin to a familiar mad waltz. The audience stands and applauds. There but for the grace of God…