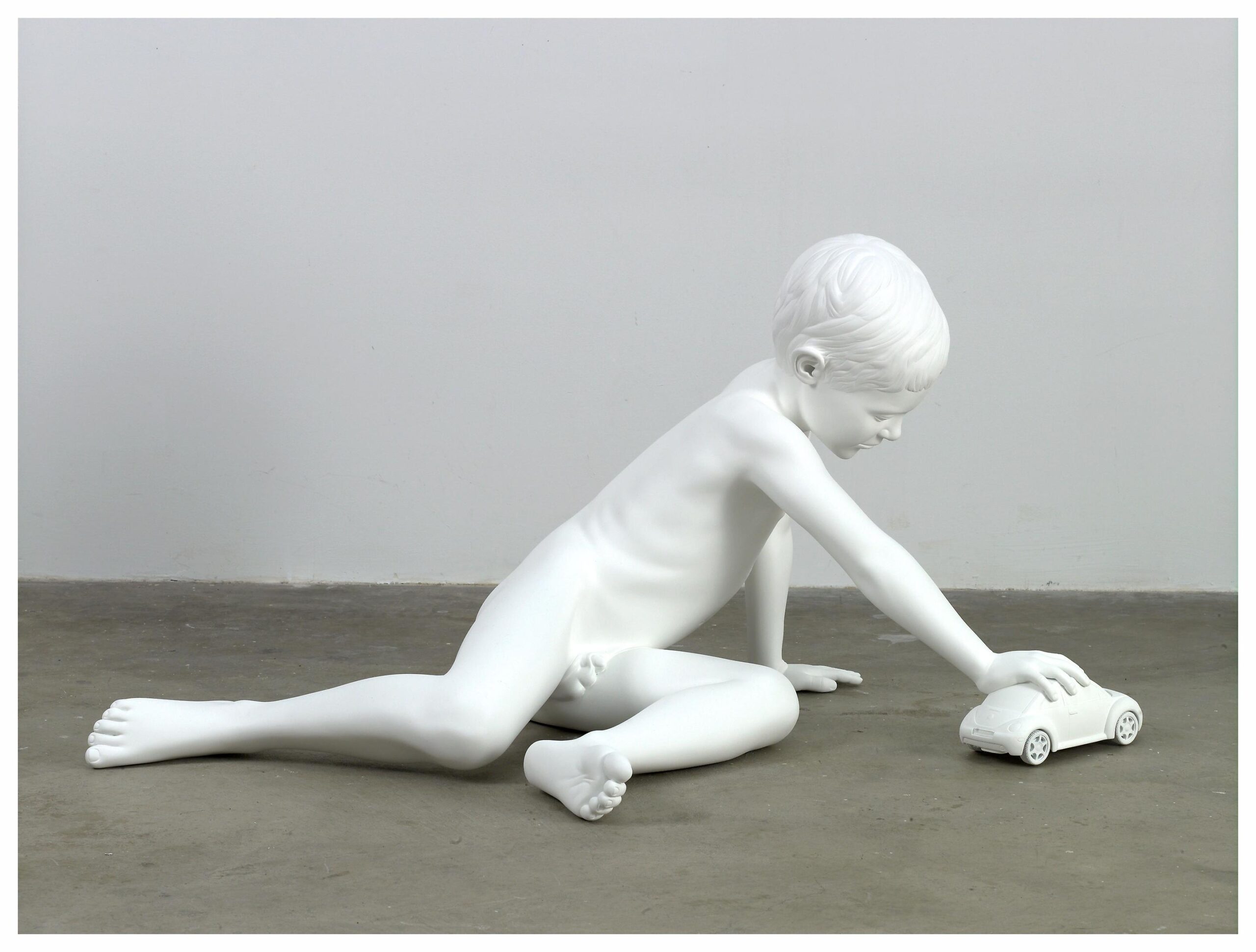

The exhibition “Charles Ray: Sculpture, 1997-2014” is elegant and unsettling. Cannily uncanny, it solicits repeated visits. A good way to approach this work may be to question the intentions of its creator, Charles Ray, who seems a trickster, a devilish prevaricator with an old master’s eye. For example, Ray writes of “The New Beetle” (2006):

The sculpture of a boy playing with his car is one of my favorites. The car is much more detailed than the boy, who is concentrating intently on his car. He is lost in play, and soon the viewer is down there on the floor with him. With all sculpture, I am interested in where you find yourself in relationship to the object. If the object can move you physically from one position — one space — to another, it will also move you intellectually.

Indeed on my first visit to the exhibition, a guard warded away a visitor in the process of getting on the floor next to the sculpture, yelling: “Don’t touch! Stay at least three feet away!” I imagine Charles Ray (who is not only the creator but also the current owner of much of the work exhibited here) having given the vigilant Art Institute staff precise instructions. The constant cry of “Don’t touch!” echoed through the Modern Wing’s second floor, as if those who had made it so far through the museum without pawing prehistoric artifacts or Picasso bronzes would suddenly be unable to help themselves when faced with the tempting work of Charles Ray. Yet the repeated warnings did serve to exacerbate the acute and certain desire to interact with this art, a desire that Ray intends to excite.

In the spacious gallery, a pale naked child sprawls on the floor with his miniature car. The detailed VW beetle is our focus because it is the boy’s. How the toy absorbs his attention. With his new toy, he is lost in play. In a painting, such absorption would fortify the fourth wall between beholder and scene, but with a sculpture, we are lured to enter the scene. We look to lower ourselves to the playing child’s eye-level. Moved physically, as Ray intends, you are also moved intellectually: You discover yourself getting “down there on the floor with him,” a naked prepubescent child. The uniformed guard yells at you: Do not touch! And you hop up, step back three feet, and ask: Why, after all, is this child naked? He isn’t so young that he wouldn’t know to cloth himself. Why is he allowing his genitals to be exposed? Has he no shame? Is he oblivious? Has he been neglected? He’s playing with a VW beetle: perhaps he’s the child of children of the 60s, parents who see clothing as a concession to conformity or public nakedness as a rebellious form of noble savagery. Is this Charles Ray’s point? But it is “the new beetle,” the 21st century model; the 60s are over, as are utopian nudist fantasies. Nevertheless the boy is lost in solitary play, oblivious to adult qualms about propriety or creepy voyeurism. And why is he so white? Perhaps he’s not at play in a prelapsarian Eden where nakedness signals sinlessness. Perhaps he crawls on the ground in a post-apocalyptic waste, covered in the dust from exploded bombs, diverting himself from the world’s end. Or maybe he is a ghost.

“Charles Ray:Sculpture, 1997-2014” (http://www.artic.edu/exhibition/charles-ray-sculpture-1997-2014 ) opened Saturday 16 May, and will be at the Art Institute of Chicago until 4 October 2015, then will move onto the Kunstmuseum Basel.