Shakespeare’s comedies are social experiments. His wild plots submit characters to the trial of whatever can happen. So he strips selves from their social identities and reveals both psyche and society to be at bottom unstable. “As You Like It” shows power to be wanton, love to be flighty and fickle, and personality to be a matter of make-believe. This last wisdom is famously expressed by the contemplative melancholic Jacques, a Hamlet-lite who’ll speak tart truths to power as happily match wits with a fool:

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts.”

The most important parts in this story are played by Rosalind. Orphaned and banished, she flees to Arden forest, masquerading as a young man. All her social identities — her class, gender, sexuality — are taken away. But even as she plays at being another person altogether, her true character is revealed. She is passionate, intelligent, eloquent and capable. Indeed, despite her own dire circumstances, Rosalind, while incognito, disabuses Orlando of his romantic fancy and teaches him the meaning of real love just in time for her to “magically” reappear and marry him. So happiness results from what the ancient philosophers called phronesis or practical wisdom, doing or saying the right thing at the right time. This, by the way, is the same virtue of timing required for telling a joke, pulling off a bit of slapstick, and putting on a Shakespearean comedy. (Such virtue is presently on display off-Broadway at The Players Theatre in Greenwich Village by the Theatre Project, whose lucidly enunciated “As You Like it,” is a madcap folk-musical romp.)

“As You Like It” does not argue, however, that virtue alone is enough for happiness. We need a little luck. Nor will the ordeal of entering Arden forest reveal hidden depths of character in everyone. Some are simply shallow. The Duke, who set in motion the play’s action by unexpectedly and unfairly banishing Rosalind, ends the play just as unexpectedly by finding religion and abdicating power. “Meeting an old religious man,/ after some question with him, was converted.” To what extremes may swing the untethered psyche! Once a power-monger dedicated to pomp, the Duke is now a cave-dwelling ascetic lost in contemplation of his own navel. Yet the happy ending of everyone depends upon the rash actions and sudden whims of such characters.

Shakespeare’s forest of Arden is a place where anything can happen. Identities may transform. Lives can change. Shakespeare acquired this disturbing perspective, I imagine, from Ovid. It is certainly not the “divine comedic” vision of Christianity, nor is it a progressive vision. It is nearly absurdist. With no inherent meaning to things, happiness can never be assured, but must remain a matter of how well we can play our parts, perhaps direct our own lives, but also requires a little luck.

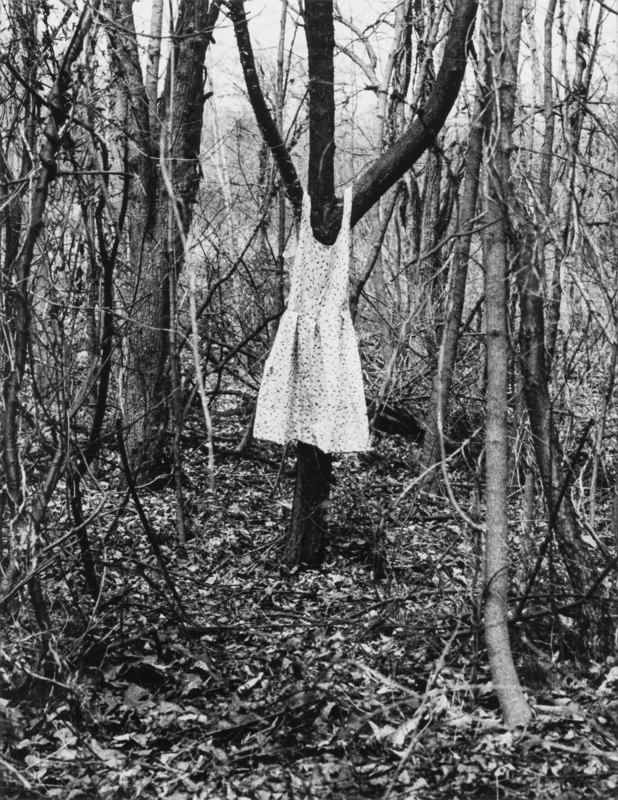

Note on the picture: Robert Gober (b.1954) and Christopher Wool (b.1955), Untitled, 1988. Gelatin silver print, Sheet, Whitney Museum of American Art.